INTERVIEW: “How we’re empowering marginalized youths in Abuja’s rural communities through sexuality education”

Linda Raji, program officer at the nonprofit Strong Enough Girls Empowerment Initiative (SEGEI), speaks about their project focused on promoting Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) among marginalized Adolescents and Young People (AYP) in rural communities around Abuja, the Nigerian capital

What does Strong Enough Girls’ Empowerment Initiative (SEGEI) seek to achieve with your Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) for marginalized youths in rural communities around Abuja?

With funding from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Swedish Government, Strong Enough Girls’ Empowerment Initiative (SEGEI) is implementing the project: “Promoting Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) Among Adolescents and Young People (AYP) in Rural Communities in Abuja” to address the lack of information on CSE among marginalized youths living in rural communities of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT).

The objectives of the project are to provide comprehensive sexuality education to 2000 in-school adolescents living in Waru and Orozo communities through monthly 40 minute classroom sessions for nine months; train and equip 50 AYP in Waru and Orozo as CSE counselors who would subsequently help youths make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive health as well as sensitize 30 community leaders and parents on the importance of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) across the two communities.

The project utilizes the second edition of the nationally approved Family Life and HIV Education (FLHE) for Junior Secondary Schools: Students’ Handbook developed by Action Health Incorporated (AHI) which provides young people with the knowledge and skills to live happy, healthy, and productive lives. FLHE has been defined as “a planned process of education that is age appropriate, culture sensitive and fosters the acquisition of factual information on reproductive health and life skills to form positive attitudes, beliefs and values to cope with the biological, psychological and socio-cultural aspects of human living.”

Topics covered by the handbook are Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS, abstinence; self-esteem; decision-making; and human emotion (love). Others are friendship; sexual violence (keeping your body safe); communication; finding help; gender and gender roles and negotiation, amongst others.

How far have you gone in providing CSE to in-school and out-of-school adolescents and young people (AYP) in your targeted communities?

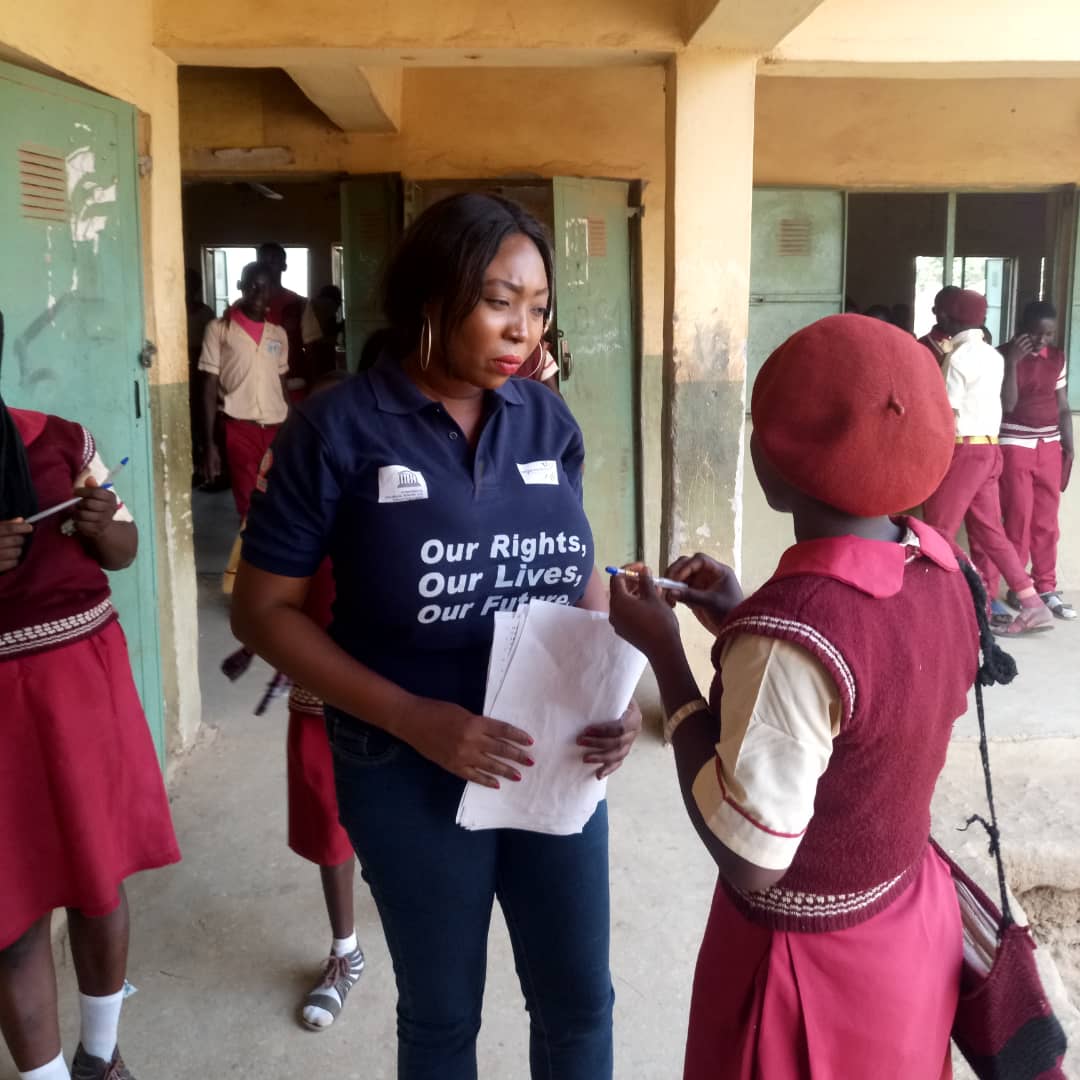

SEGEI has adopted UNESCO’s Our Rights, Our Lives, Our Future (O3) campaign whose objective is achieving sustained reduction in new HIV/STI infections, early and unintended pregnancy and gender-based violence by empowering adolescents and young people to develop the skills, knowledge, attitudes and competencies needed to sustain positive education, health and gender equality outcomes. We have been promoting CSE among marginalized youths in Waru and Orozo communities to help them make informed decisions and lead healthy lives.

As a program officer, I led the SEGEI team in the last two months to successfully sensitize over 30 youth leaders and parents on the benefits of CSE as well as trained 50 out-of-school youths as counselors in the two respective communities whom other adolescents and young people can approach to help them make informed decisions. We have also sensitised 1000 in-school youths and 300 out-of-school youths on topics such as decision-making, HIV/AIDS and other STIs prevention. This monthly outreaches, which are based on carefully selected topics, will continue up until July 2019.

What will you say have been your greatest challenges working with the adolescent youths at the grassroots?

Many of the youth leaders and AYP in these communities expect to be paid to attend the outreaches. Therefore, the team made successful efforts of mobilising them to attend the outreaches which are essentially about lifesaving information for them. We achieved this by changing their mindset away from thinking of being paid to attend outreaches within their own communities and which are aimed at their positive wellbeing; the youth leaders influence the attitude of the youths of their communities.

Moreover, getting the male out-of-school youths to attend outreaches was also challenging, initially, as they were too busy with income-generating and fun-seeking activities to attend the outreaches. To address this challenge, the team came up with the idea of meeting them at the football field, after their footballing sessions in the evening, as well as visiting them during their community meetings. This approach really helped us got the male out-of-school youths to begin to attend our outreaches.

Any outstanding success stories from the project?

The project has recorded a number of success stories, the first success story unfolded during our the first outreach for out-of-school youths; when a 23-year-old lady who was a Junior Secondary School [JSS2] dropout that became a teenage mum when she was 17 confided in one of our team members her wish to be able to write down her thoughts, as the questionnaire was being read out for her. The team member reminded her of her right to an education and encouraged her to return to school, which is currently being processed.

Another incident happened during one of our sessions for out-of-school boys when all the boys told the facilitator they didn’t see the need for girls to be sent to school since they will eventually be married off; they felt educating girls was a waste of investment. However, by the end of the session, the facilitator had successfully influenced a change in their mindset about the gender bias. Again, during an in-school session, a teenage girl privately asked a facilitator about how to handle a sexual harassment she had been facing for a while from a neighbor and she was given practical steps to take and was able to successfully address the challenge.

Just last week, a 13-year-old girl in one of the schools we work gave me a feedback on an issue she confided in me last November, after our first session on decision-making and just before their school went on vacation. She was actually being sexually harassed on her way to school daily and I counseled her about how to handle the young man. This January, upon her resumption to school, she happily told me how relieved she was which also made me felt fulfilled. There are many other such stories. These kinds of stories make our work of helping young people make informed decisions a fulfilling one.