COVID-19: CHRICED report on Almajiri repatriation recommends reform of Almajiri system

The Resource Centre for Human Rights and Civic Education (CHRICED) report on the recent repatriation of Almajiri children by various governments of northern states, against the backdrop of the outbreak of COVID-19, makes far-reaching recommendations on reforming the Almajiri system

The nonprofit say the report titled: “COVID-19, Repatriation and Human Rights Violations of Almajiri Children in Northern Nigeria,” is a prelude to a still ongoing research by CHRICED and the Anti-Slavery International (ASI, United Kingdom) on “Eradicating Drivers of Forced Child Begging in West Africa with focus on the nature and effectiveness of state and non-state interventions in Nigeria.” The report is also part of CHRICED’s project focused on “The nature and effectiveness of state and non-state interventions on Forced Child Begging (Almajiri) in Nigeria.”

Thus, the report explores various issues around the Almajiri children repatriation exercise carried out in the context of an existing inter-state ban by the federal government, as part of efforts to curb the spread COVID-19 in Nigeria. Amongst others, it highlights the state governments’ abuse of the rights of the almajiri children; the often-negative stereotypes and profiling of Almajiri children in the mass media; the negative impact of confinement of Almajiris resulting from lockdowns on towns and cities across northern states; the illegality and unconstitutionality of repatriation of Almajiri children; as well as the Almajiri chidlren’s right to free and compulsory education.

The CHRICED report observed that the COVID-19 pandemic had heightened the abuse of the rights of thousands of Almajiri children by northern state governments, as they grapple with the period of uncertainty occasioned by the coronavirus. The report says, in their attempts to contain the spread of the virus, governors of the northern states have reverted to blaming Almajiri children for their own failures to contain the epidemic, depicting the hapless children as key vectors of the transmission hence, the series of inter-state repatriation exercise.

“The onslaught against almajiri children, notably evidenced by the raids of task forces ordered by local state governors’ defies the response, protocols and strategies of the federal institutions leading the fight against COVID-19. These raids were merely knee-jerk reactions meant to scapegoat almajiri children and depict them as disposable high-risk carriers of the virus. It is pertinent to mention that Nigeria, through the Presidential Task Force (PTF) and the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) rolled out a number of guidelines and protocols to prevent the spread of the virus; and to safeguard the lives of citizens while respecting their rights,” said CHRICED.

Governors abuse Almajiris; media stereotypes them

The CHRICED report noted that, in defiance of guidelines put in place by federal authorities, and in utter violation of COVID-19 protocols, the respective state governors continued to infringe on the human rights of almajiri children, by transporting them from one state to another in rickety and ramshackle trucks, without any clearly defined protocols, and with zero respect for social distancing and personal protection measures.

As a result, the report say despite the repatriation measures, “the reality on the ground in many states suggests the removals were merely attempts to create the false impression that actions were being taken to stop the spread of COVID-19. In Kano State for instance, the removal of Almajiris who are allegedly from other states, if effective should have meant fewer number of destitute children roaming the streets of the state. However, this is not the case as thousands of Almajiri children are still roaming the streets of Kano.

“This demonstrates the ineffectiveness of the repatriation, especially because a significant number of Almajiri children were expatriated from other states to Kano. What this shows is that nothing has actually changed in substantial terms, as state governors are unwilling to do the real work, which would involve taking clear responsibility for the task of getting the children off the streets, ensuring they reunite with their families, and creating the framework for them to access basic education which falls within the purview of the states.”

In addition, CHRICED say one of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Almajiri is the negative stereotypes and profiling of Almajiri across different channels of the mass media, which represent them as invaders who would pose security threats to southern part of Nigeria. The report, which provides many instances of how the media platforms portrayed the Almajiris through lenses of marginalization, however, says the geo-ethnic profiling of marginalized victims of the Almajiri system makes advocating for their cause quite challenging.

Almajiri and lockdown measures

Additionally, the CHRICED report says the lockdowns imposed by the federal and respective state governments across northern Nigeria, in a bid to curb the spread of the virus, had taken a serious toll on the Almajiri children, who are predominantly aged between 5 and 12 years. It noted that the confinement resulting from lockdowns on towns and cities had an unbearable effect on the children’s food security, due to lack of a clearly-defined response plan to protect the over-9.5 million Almajiri children roaming the streets of major towns and cities in Northern Nigeria, despite their constituting one of the most vulnerable groups of the region’s social fabric.

CHRICED said although the Federal House of Representatives had, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in March, passed an economic stimulus law, however, there was no mention of members of vulnerable groups such as the Almajiris in the law. “Despite their squalid living conditions and their mobility, which make them highly susceptible to contracting and spreading the virus among themselves and others, there were no specific Almajiris-targeted awareness, protection and support interventions, as part of the government’s larger response initiatives to COVID-19,” says the report.

The report said consequently, many Almajiris got infected with COVID-19, prompting the knee-jerk decision of governors of northern states under the aegis of the Northern Governors’ Forum (NGF), to ban the practice of Almajiri system of education (Almajiranci) in northern Nigeria, followed immediately by the controversial Almajiri repatriation campaign across the region – instead of offering them psycho-social, medical and feeding support during the emergency.

Amongst others, the objectives of the Emergency Economic Stimulus Law which seeks to provide aid to in-country businesses and individuals, are to: provide temporary relief to companies and individuals so as to alleviate the adverse financial consequences of a slowdown in economic and business activities caused by COVID-19; protect the employment status of Nigerians who might otherwise become unemployed as a consequence of management decision to retrench personnel in response to the prevailing economic realities.

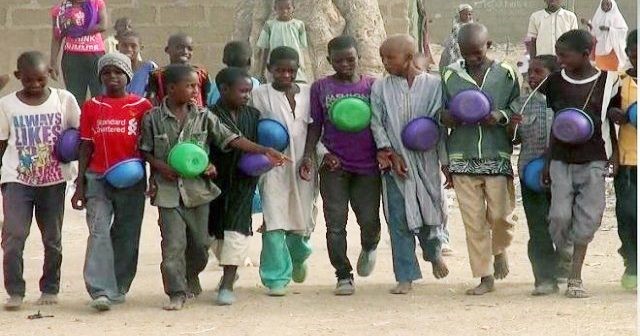

A group of Almajiris with their begging bowls wandering in search of alms Photo: Financial Trust

Repatriation illegal, unconstitutional

The CHRICED report says whereas the 1999 Nigerian constitution (as amended) recognizes the concept of indigeneity, it however also guarantees the fundamental human right of all Nigerian citizens to move freely and reside in any part of the country as they wish. Consequently, it says the entire idea of “repatriation” or “deportation” as it relates to the movement of citizens within the Nigerian federation is alien to and unrecognized by the constitution. Thus, it describes the NGF’s action as “an inhumane violation of the children’s fundamental human rights, as enshrined in Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria officially known as Fundamental Rights.”

The report adds that although the northern states claimed the repatriation exercise was intended to minimize the children’s exposure to the disease and prevent further community transmission of COVID-19, “in reality, the repatriation of Almajiris who had been infected with the virus in their states of residence to their states of origin eventually led to further spread of the coronavirus across northern states, worsening the crisis situation in the region. These could have been avoided if the governors had found it necessary to protect and care for, arguably the most vulnerable cluster of people in their states.”

As it had been the practice since the commencement of the deportation exercise, all Almajiris that have been repatriated to their states of origin are subjected to medical screening and quarantined by their home states in designated camps for a period of two weeks – to determine whether or not they had been infected with COVID-19. At the end of the confinement, those who tested negative for the virus are handed over to their parents, while those who tested positive receive treatment. However, the CHRICED report descried the poor sanitary condition of quarantine camps of the Almajiris in their states of origin.

“Consequently, thousands of Almajiris are currently being kept in isolation centres across the northern states. Whereas the idea of the quarantine camps is to ensure Almajiris who have been infected with the coronavirus do not go back home and infect their families with the disease, the very purpose of these camps seems to have been defeated. Indeed, Almajiris, who are supposed to be protected and cared for in accordance with the best medical practices necessary for curtailing the spread of the virus, are instead living in the same squalid and dehumanizing conditions they had left in their various states of residence,” the report said.

Almajiri’s right to education

The report acknowledges Nigeria’s signing and ratification of most international conventions aimed at protecting the dignity and welfare of children, by guarding them against various forms of abuse including neglect, exploitation, trafficking and very importantly, ensuring children have access to basic education. Among such instruments, reports says, are the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the African Union’s African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC).

The CHRICED report also noted that the Child Rights Act (CRA) was enacted in 2003 based on the UN and OAU/AU conventions; it however says the state governments of the Nigerian federation had “insisted that it would only be effective if the respective State Houses of Assemblies domesticate and ratify the law. Seventeen years later, barely two-thirds of the 36 states of the federation have ratified the Act. Sadly, most of the states that are yet to domesticate and ratify the CRA are in the northern region harboring Almajiri children.”

Moreover, the report underscored the significance of Nigeria’s Universal Basic Education (UBE) programme, which aims at providing greater access to and ensuring quality of basic education throughout the country including ensuring an uninterrupted access to 9-year formal education by providing free, and compulsory basic education for every child of school-going age under six years of primary education, and three years of junior secondary education as well as providing Early Childhood Care Development and Education (ECCDE).

Consequently, the report say the above laws have made providing access to free basic education for every Nigerian child obligatory on the federal and respective state governments, including almajiri children. It therefore says whereas the idea of a total ban for the practice of Almajiranci by some sections of the society may sound good, the question is what happen to the over 9 million children that are currently in the system if it is abolished? Another question the report poses is what measures have been put in place to ensure the Almajiri schools will not reemerge as they have always done in the past?

Reforming the Almajiri system

Accordingly, CHRICED say what might be the best response to the current dysfunctional Almajiri system, is a comprehensive and actionable reform programme, based on similar systems of Islamic education obtainable in Muslim countries such as Egypt, Malaysia and Indonesia. However the report says “in doing so, Nigeria must avoid the traditional ready-made approach to adopting foreign systems and policies and adopt and adapt, instead, the lessons to be derived from these developments to suit its local context.”

Against the backdrop of a lack of awareness and perceived ineffectiveness by target beneficiaries of state and non-state interventions on forced child (Almajiri) begging in Nigeria, the report made far-reaching recommendations on reforming the Almajiri system namely that “governments at all levels must ensure the enforcement of existing laws relating to forced child labour and street begging” adding that they should also “ensure that Almajiri school teachers who exploit children in anyway are prosecuted and subject to sentences that are proportional to the crimes committed.”

Furthermore, the report recommends that “the curriculum of the Almajiri schools needs to be transformed to reflect present day realities and future aspirations of the society in which the Almajiri children live” adding that “the new curriculum should be a blend of Islamic education, Western education and life support skills such as ICT that can help the children cope effectively with the realities of modern world, and to fit properly into the future they aspire for.”

It also calls for “the proper regulation and documentation of Almajiri schools. This means a special unit should be opened in every state to collate data on the actual number of Almajiri schools and the children enrolled in those schools” noting that “Malams willing to establish and operate Almajiri schools must register with the appropriate authorities to ensure proper supervision and periodic inspection.

CHRICED also says “some measure of parental responsibility has to be enforced. In this regard, local communities, religious institutions, governments, civil society groups and other critical stakeholders need to find ways of sensitizing and mobilizing the parents of these Almajiri children to be more responsible.” The report said this had become necessary in view of the fact that no level of intervention by other stakeholders i.e government, NGOs, Civil Society, religious institutions etc can totally substitute the role and place of parenting in a child’s upbringing.