COVID-19 and the poor communities of Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital

The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated some of the best healthcare systems in the world. Consequently, the world has been anticipating a potentially disastrous rampage in Africa, where most countries are grappling with fragile and poorly managed healthcare systems.

Thanks to a relatively late arrival and a slower course of spread, COVID-19 is yet to overtly annihilate Africa’s fragile health systems, thus the continent still has a window of opportunity to avert a disastrous health crisis.

Subsequently, African nations have enacted complete lockdowns of major towns and cities, encouraged voluntary isolation, closed down schools, and religious institutions, as well as promoting social distancing as a means of containing the spread of the virus. Countries like Senegal have taken the German approach, opting for universal testing. But, considering the scarcity of testing kits and referral labs across the continent, it is difficult to fathom this being applied to the whole of Africa.

Feared equally, if not more, is the economic impact of the pandemic. Various economic forecasts are being made on the economic consequences of the pandemic on Africa, and it doesn’t look good! Flattening the curve seems to be the best strategy for the prevention of the disease. However, African leaders are contending with the challenge of running equally fragile economies with high unemployment rates. Consequently, majority of their citizens are feeling the heat of the pandemic-induced economic depression, owing to the fact that majority of employees have either had their salaries cut down or even completely laid off.

Ethiopia is no exception; its first case of COVID-19 was reported three months ago, now the number of confirmed cases stand at over 5000, a figure that is by far lower than initial projections. Taking advantage of the unexpected development, the government has now stepped up its efforts by increasing the numbers of testing, treatment and quarantine facilities. Recently, there has been concern about the astronomic rise in the number of COVID-19 daily infections, approximately by 300 folds.

However, the government is yet to impose stringent movement restriction measures, solely for the fear of the economic implications of such measures on its citizens; however, they couldn’t completely avoid the economic consequences of the pandemic. Majority of the Ethiopian capital’s workforce comprises of low income earners with little to no savings at all. These are the people bearing the brunt of the economic fallout of the pandemic.

With citizens being encouraged to work from home and curtail social engagements, there’s a palpable decrease in the number of people on the streets of Addis Ababa, leaving street vendors and shoe-shiners with less customers. Cafes and hotels have been forced to lay off their staff or cut down the wages of already underpaid employees, daily laborers such as construction workers are indirectly feeling the impact as investors and companies slow down construction works, housekeepers and washer women are being denied their daily earnings as people are afraid to let them into their homes.

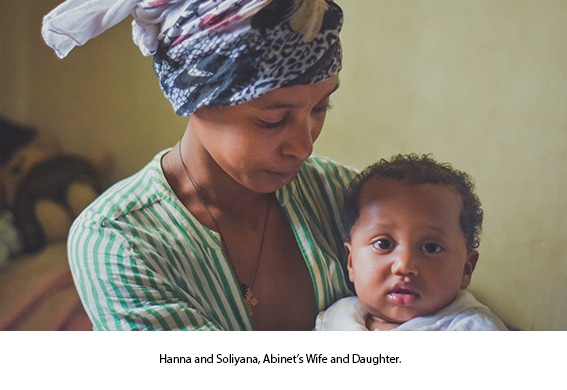

Ato Abinet, husband and father of a 10-month-old baby, is a former bartender at a bar in down town Addis, he was laid off a month into the pandemic when the government asked bars to be closed for the unforeseeable future. He says he has been looking for a new job for the past two months to no avail. Adding to his misfortune, new transportation rules set to lessen passenger congestion in public transport meant fares have been doubled. “I feel completely out of sorts here, I’m thinking of moving back to the countryside with my family” Abinet says.

Not very far from where Abinet lives, Tigist, a single mother of three, makes a living providing manual laundry services in neighboring homes as well as selling tea on the street. Her tea business went flat the same week Ethiopia reported its 1st case of COVID-19, and now people are refusing to let her into their houses to provide laundry services. “I didn’t know what to feed my children [with],” says Tigist, who has sent her children to her family in the countryside. “At least they won’t have to sleep hungry there.”

In contrast, a minority have managed to outmaneuver their fates. Street vendors have in large supply the now in high demand commodities – sanitizers, gloves and masks – while tailors reshape to profit from cloth-mask production. This episode of global ‘enochlophobia’ has also boomed the business of contract taxis as people avoid the crowds of mass transport. It is evident that the government is struggling to mitigate the economic and health fallouts of the pandemic. Across Ethiopia, many fundraisers have been launched to support the government’s efforts.

Folks are also coming together to keep the less fortunate afloat. Social organizations and charity groups have set out to provide essentials to underprivileged communities. Various awareness campaigns are underway emphasizing personal hygiene and social distancing. The one-month old state of emergency forbidding companies from laying off staff has somehow alleviated the fear of the people but doubts lie on how successful the measures will be, as the country’s economic woes precede the coronavirus crisis.

Natnael Z Shimelash Natnael is a freelance photographer/photojournalist based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. His work focuses on what he perceive as stories that need to be told, about the Ethiopian people, culture and history.