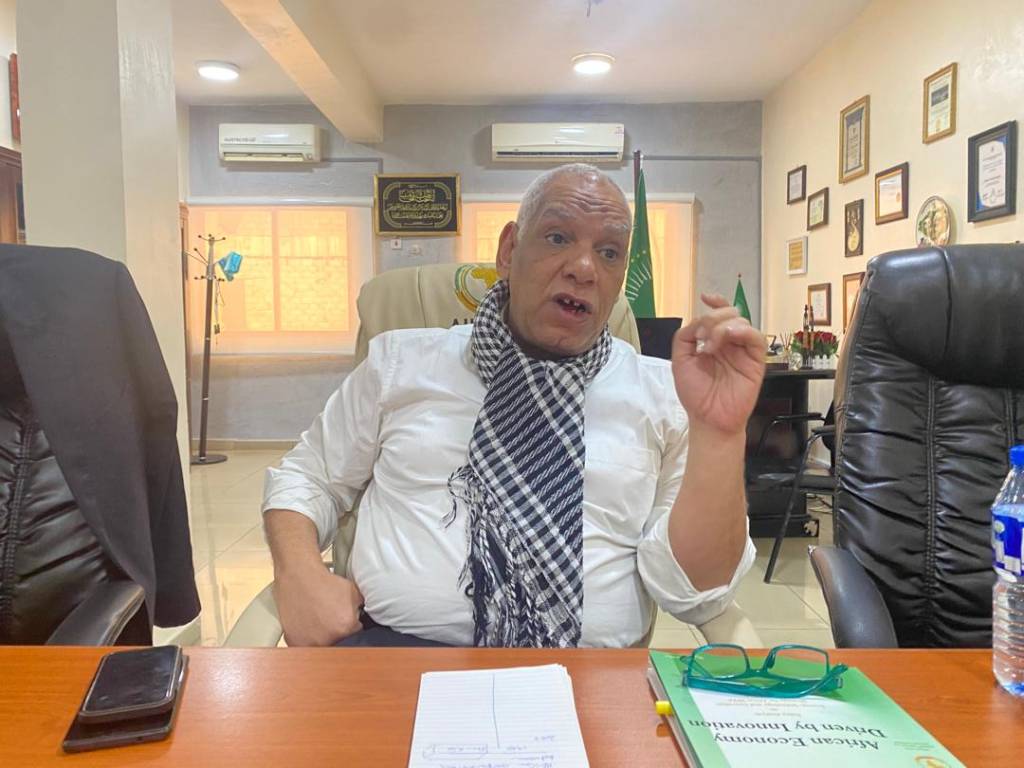

INTERVIEW | “Only Domestic Funding will Help Africa Create Prosperity through STI” – AU-STRC

Dr (Engr) Ahmed Hamdy, Executive Director of the African Union Scientific, Technical and Research Commission (AU-STRC), decries Africa’s low-level funding for Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) which inhibits its development.

Newspage: The AU-STRC is mandated to promote the role of science, technology and research in strengthening cooperation and bringing about the development of AU Member States. How far have you gone in achieving this crucial mandate?

Dr Hamdy: The AU-STRC was founded before the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) itself and was subsequently integrated into the OAU system in 1965 as the leading institution for the promotion of science and technology on the continent. We therefore support and contribute to research across a spectrum of disciplines, including engineering, agriculture and public health, among others.

In 2003, the institution was again integrated into the then newly established African Union (AU), as a specialized agency mandated to support Member States in the area of Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) as well as Research and Development (R&D). We are therefore mandated to support Member States to utilize scientific research and innovation for development and self-sustainability. To this end, in 2007, the AU initiated the African Union Research Grant (AURG) to support scientists from its Member States to collaboratively carryout research through grants and direct funding.

One of the criteria for the grant is that 2 out of the 3 grantees must be from the least developed countries – which means you can’t have scientists from, say, Egypt, South Africa and Nigeria. Again, you can’t have scientists from Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt who are from the same region. Thus, the objective of the AURG is to foster integration through scientists and help the Member States better leverage their comparative advantages in STI. Therefore, each research grant must address at least one of the development issues bedeviling the continent, such as energy and infectious diseases.

In 2018, we set up the African Scientific, Research and Innovation Council (ASRIC), a pan-African platform that builds and sustains a continental research-policy nexus. In the same vein, we are working to foster collaboration among African scientists and institutions through ASRIC. For instance, if the Nigerian Academy of Science (NAS) is interested in doing research on AI in agriculture and the Kenyan Academy of Science (KAS) is also interested in the same, the different countries can develop a strategy for co-financing, co-researching, co-publishing and co-owning the Intellectual Property Rights (IPR).

Moreover, the annual Congress of ASRIC offers a platform for African scientists to exchange ideas, sign mutual agreements and build the capacity of one another beyond which they can exchange visits with one another. In essence, we are doing well in the area of integration among our academies and universities in the areas of Science, Technology and Innovation (STI).

However, the reason why partnership and cooperation among African science academies and universities is being slow has to do with the challenge of financing. In other climes, such as Europe, they have initiatives such as Horizon 2020 and 2023 on which they spend billions of euros on financing research and innovation. They invest these resources in bilateral cooperation and building capacities of each other, as well as building on their various comparative advantages.

On the other hand, the program funding for ASRIC in the last 5 years is very meager from AU Member States. We are therefore relying on co-financing and other alternative sources of funding with which we are currently funding research in Industry 4.0 that attracted sponsorship of 43 PhDs under full scholarship at Euromed University in Fez, Morrocco.

The reality is that external funding will not solve Africa’s problems. So, unless and until African resources are invested in STI, we will not be able to create the prosperity we desire. We no doubt appreciate the role of external partners. However, as they say, your hand should already be in your mouth before others can bring you their own food to put in your mouth. This is a basic commonsense we need to teach ourselves.

Newspage: The Science Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa 2024 (STISA-2024) strives to place STI at the centre of Africa’s development. What progress has been made in implementing STISA-2024 now that we are already in 2024?

Dr Hamdy: STISA-2024 is implemented by different departments and organs of the AU because STI cuts across many sectors. When we received the STISA document, we came up with our own strategy for implementing it in the form of the ‘African economy driven by innovation’ published in 2016. We adapted the STISA-2024 document from a strategic framework to an implementation framework. This is because strategies only paint a vision, mission and outcome but don’t provide the pathway towards achieving the grand outcome.

We therefore analyzed the pillars of STISA-2024 and also identified the areas of interest for AU-STRC in the document. The strategy defines four mutually reinforcing pillars which are prerequisite conditions for its success, namely building and research infrastructures; enhancing professional and technical competencies; promoting entrepreneurship and innovation; and providing an enabling environment for STI development, which is the role of STRC.

Accordingly, since the commencement of the implementation of STISA-2024, STRC has mobilized over 12,000 scientists to work together to address Africa’s development challenges through STI. We have over 20 flagship projects that cover a wide spectrum of issues from Covid-19 and Hepatitis to AI as well as agriculture, among others. We have many projects geared towards helping and serving the people of Africa.

Newspage: According to AUDA-NEPAD, to achieve STISA-2024, African governments must create a strong political will and trust in the intellectual capacity of African citizens, revamp their STI infrastructure and take measures to curb brain drain. Why are African countries struggling to provide enabling environments for STI and entrepreneurship to flourish?

Dr Hamdy: The question we need to ask is, are politicians ready to invest in STI? Investment in STI is not something that politicians can use as a campaign promise in our clime. For instance, no politician would want to say they will invest 5% or 10% in STI or R&D if elected into office because it is not a powerful campaign issue. The electorate will not be impressed by such a pledge.

To address this challenge, the politicians themselves need to be enlightened on the role of STI in development. And this is one of the roles of the Science, Technology and Innovation committees in our national parliaments. They need to advocate and sensitize their fellow parliamentarians about the importance of investment in STI. The challenge requires lots of efforts to be addressed, and we are continuously doing so.

Newspage: STISA-2024 was part of the First Ten Year Implementation Plan of AU’s flagship development framework i.e. Agenda 2063. Now that the FTYIP is being reviewed and the STYIP is being designed, what happens to STISA 2024?

Dr Hamdy: Strategies do not expire. Strategies can work for a longer time than they were meant to work. The vision of STISA 2024 is the same as that of Agenda 2063 and its mission is to be able to achieve a certain level of development in STI within the first 10 years of Agenda 2063.

The STISA for the upcoming 2024-2034 decade will build on the experiences of STISA-2024. There is already a group of scientists and science policy experts working with the AU Commission to finalize the STISA for the next decade, which will soon be ready for the Heads of State and Governments’ approval. I am optimistic that the new phase of STISA promises a lot and may eventually advance STI in Africa.

And to curb the brain drain, you have to increase the remuneration of scientists, working conditions, environment, among others, which will attract quality scientists back to the continent. With an attractive package, scientists will be willing to stay longer and work in their home countries. This happened in Pakistan in 2004/2005 when they implemented a back-home integration system which basically meant increasing the wages of scientists to allow them the opportunity to live their desired lifestyle when they returned home from developed countries.

The other thing is, can we completely stop brain drain? The answer is no. Instead, we should be focused on creating brain circulation in Africa. This means building bridges between local scientists and scientists abroad to allow them to engage in joint research projects. This is necessary because freedom is the mother of creativity and innovation. A man who is able to move freely has a capacity for creativity and invention. We are now working towards setting up a committee of African scientists to work on brain circulation policy for Africa.

We already have the African Union Network of Sciences (AUNS), a virtual network of 12,000 scientists, engineers, technology developers, innovators and inventors from all over the continent and the diaspora which promotes joint research projects and capacity building between home-based and diaspora scientists. So, we need to be innovative rather than keep complaining about our problems. Stopping scientists from migrating will not work. Moreover, we should provide them with incentives to come back home and work.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity